Purple martins are North America’s largest swallow, members of the family Hirundinidae, which includes the swallows, martins, and saw-wings. In the Old World, the more square-tailed species are called martins, while the name swallow usually refers to the fork-tailed members of the family (like barn swallows), though the shape of the tail does not represent any real evolutionary difference. In the New World, only members of the genus Progne are called martins. In the United States we have only the purple martin, Progne subis. Brown-chested martins (Progne tapera) are very rare visitors from South American. Our purple martins are actually blueish-black, but with iridescent feathers they can appear purple. Like all swallows, purple martins are agile aerial insect hunters.

Each August our purple martins congregate in huge roosts with the newly fledged birds joining the adults in preparation for their migration to their winter grounds in South America. With tens of thousands of birds flying arriving over the last hour or so of daylight, it is quite the spectacle - difficult to capture in a still photo. Video gives a much better sense of just how many birds are present.

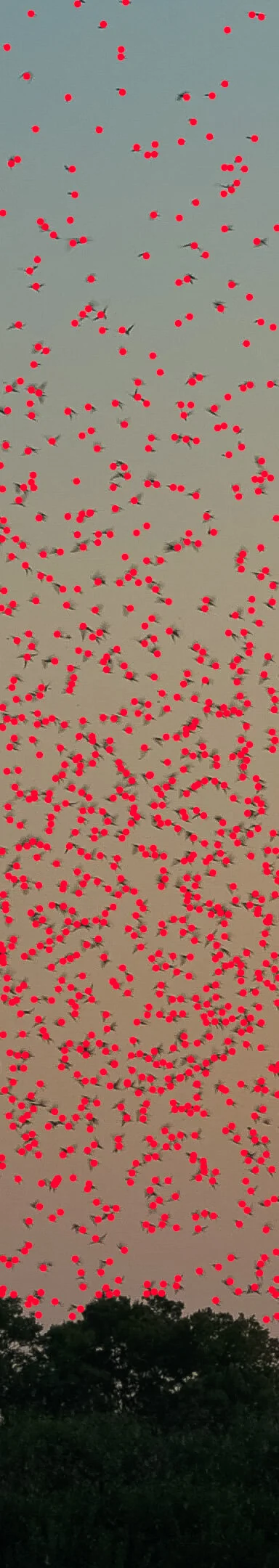

To get an approximate count, I chose one typical frame of the video as a baseline. Counting that many birds looked like a daunting task, so I took just one-tenth of the image. I keep track by putting a dot on each bird using Photoshop. There are 902 red dots in this partial image! That means the full frame includes about nine thousand birds. That is just one small section of sky, though. I estimate I could have taken three full, non-overlapping frames with a similar density of birds in the main flock, so twenty-seven thousand is our starting point. Add to that all the thousands of birds arriving from all directions - less dense, but easily ten more frames with one to three thousand birds each, so add another ten to thirty thousand, and we are looking at somewhere on the order of thirty-five to fifty-five thousand birds. And we haven’t considered the ones who have already settled in the trees. Those are rough estimates, of course, but I don’t think I’m off by orders of magnitude. It is a bad time to be a flying bug in Prospect, Kentucky!

In a couple weeks these birds will begin breaking into smaller groups to head south until they return next year in late March or early April, some of them to the hollow gourds and nest boxes provided by Homo sapiens. If you’ve ever wondered why we do that, it is not merely because we like to watch them. Early American settlers put out gourds and nest boxes to attract purple martins because they are aggressive toward hawks and crows, and thus helped protect their chickens from predators.

So, look to the skies this month and if you find a large roost, hang out and watch for a while. It’s worth it!

Thanks for reading,

Greg

902 red dots in a one-tenth width slice of the image!